The Problem with Toys

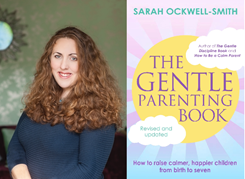

By author, Sarah Ockwell-Smith.

Many parents despair of their child's inability to play alone for any length of time, or the speed at which they get bored with toys. The biggest problem with most toys today is that their play appeal is limited. A shape sorter is just a shape sorter: put the shapes into the holes and the toy no longer offers interest. An entertainment centre loses appeal after the buttons have been pushed, the beads moved along, and the xylophone chimed.

Most toys have a specific purpose that doesn't allow the child to explore. When the child bores of the set purpose, the toy no longer holds appeal for them.

As children grow up, the overprovision of toys can stifle their imaginations. The overwhelming choice of playthings offered to most children today is perhaps one of the worst curses of modern childhood. I often hear parents mutter, 'You should be grateful you have so many toys. In my day, I didn't have half the amount you have.' But these parents are the lucky ones: their childhoods were likely filled with the amazing games of make-believe that their own children lack. Studies conducted by German researchers Elke Schubert and Rainer Strick found that removing toys from children results in them becoming more creative and more social.

In their experiment, entitled 'Der Spielzeugfreie Kindergarten' ('The Nursery Without Toys'), all toys were removed from children for a period of three months, the only items left being chairs and blankets. Initially, the children were bored; however, they quickly readjusted and were soon building dens and enjoying the new set-up. By the end of the experimental period, not only were the children playing imaginatively and creatively, they were also more confident and social with each other, with better interpersonal relationships and less friction and fighting between themselves. This led the researchers to conclude that children can be 'suffocated' by the presence of toys and also find it harder to concentrate when surrounded by them.

While the idea of having a completely 'toy-free' home may fill you with horror, there are some points from Schubert and Strick's research that can be implemented with ease. Firstly, thin out the toy supply - removing those items that are barely or rarely played with. Next, consider rotating toys. At the end of the experiment, toys were reintroduced to the nursery and the children were happy to see them return (the saying 'absence makes the heart grow fonder' applies to toys too!), so rotating your child's toy supply and putting some away in a cupboard for a month or two, so they remain fresh is a great idea. Lastly, never underestimate the play value in everyday objects. In the experiment, it was simple chairs and blankets, but there are many other options. Here are some examples:

* Cardboard boxes - so many possibilities: anything from spaceships to houses.

* Old handbags and purses - great to fill with treasures.

* Cornflour and water - makes a wonderfully intriguing, gloopy blend.

* Mud, mud glorious mud: mud pies, mud modelling, mud kitchens and more.

* Water - freeze toys in ice, 'paint' with it on pavements, make boats to float.

* Den building - inside with blankets and sheets, outside with sticks and branches.

* Bubble wrap - put it on the floor and jump and roll on it (make sure you supervise this one!)

* Plastic cups - great for stacking, pouring and scooping.

* Old phones and remote controls - pressing buttons and pretending to control things.

* Old baby wipes boxes and tissue boxes - great for 'posting' things and sorting.

Excerpt from 'The Gentle Parenting Book' by Sarah Ockwell-Smith, reproduced with permission.